The Tale Of THE TALE OF THE TALE OF TALES

This past summer I spent six weeks in southern Italy teaching a Princeton Global Seminar on Storytelling and Musical Theater. The class culminated in a production of an original piece of musical theater based on The Tale Of Tales by Giambattista Basile — the oldest collection of literary fairy tales in the Western canon. The students (along with three professional actors from America and two local Italian actors) performed in a musical I wrote about the life of Giambattista Basile and his sister Adriana, a famous opera singer. In addition, the students also wrote and performed for an installation based on Basile’s fairy tales, with each room in a large palazzo hosting a different story. If that sounds like a lot to accomplish in six weeks, it was! And this was in addition to a seminar on Broadway musicals led by Professor Stacy Wolf, Italian language classes, and hours-long meals every day!

Anyway, I recently got the chance to make demo recordings of some of the songs I wrote for this project, and thought I’d share them here… along with any thoughts I have about them.

This was the opening number. When I started working on the show, I listened to a lot of Neapolitan folk music, and there was one particular song — the Tammurriata Nera — that I knew I wanted to draw from. (Jump to a minute or so into this video.)

It had this relentless, galloping drive to it that, to me, sounded like “tale of a tale of a tale of a tale…”. That was the lyrical hook I had in mind, because the fairy tale collection itself was already called “The Tale Of Tales,” and our show was going to tell the story behind its creation — thus, the tale of “The Tale Of Tales.” This, in turn, led me to a song format where one verse would introduce the frame story of the collection, another verse would go deeper in and talk about all the stories within that frame, and another verse would zoom out and talk about the story of how this collection came to be. Because of the layers of story, the “Russian doll” simile came to mind… and led to one of my favorite rhymes here… (though the near-rhyme of Byzantine and Dis-uh-ney is an honorable mention.)

The notion of creating an original American musical to be performed for a local audience in small-town Southern Italy (where there are not many English speakers to be found) was a bit odd, I’ll admit. Should we subtitle the whole thing…? Should I try to translate scenes and songs into Italian? Would students be able to perform in Italian?

The compromise we arrived at was that songs were, for the most part, in English, while scenes were translated into Italian, performed by our two local actors who were playing Giambattista and Adriana Basile. These two roles were doubled by two of our American professionals when they sang. We did, however, have a few short song moments that were in Italian and performed by our American students — “Le Tre Corone” being one of them.

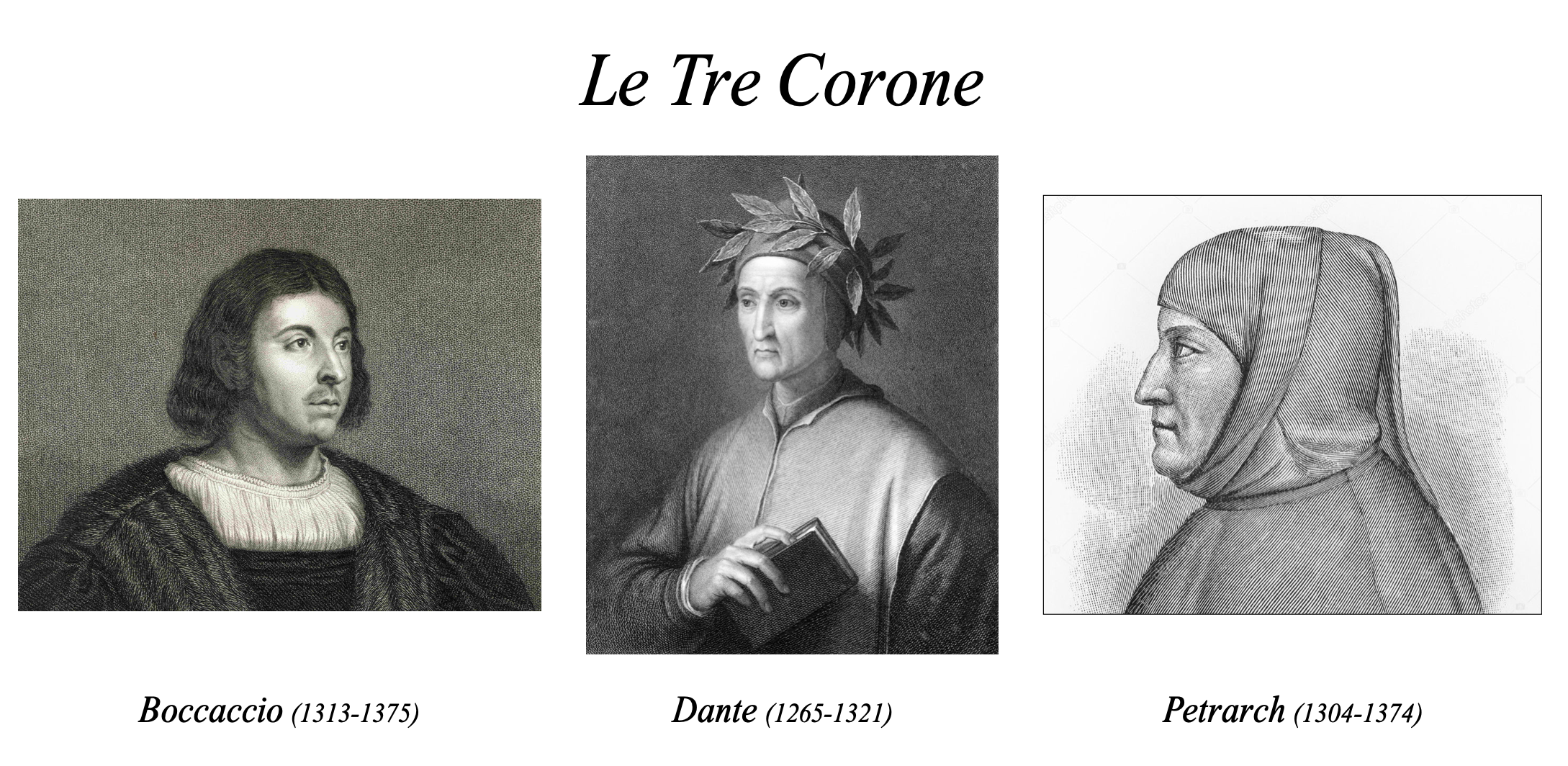

The song introduces Dante, Boccaccio and Petrarch — three exalted figures of Italian literature, who wrote in the Tuscan dialect and helped establish that as proper “literary” Italian (and later, after unification, the only Italian.) Throughout the story, these three literary giants haunt and harass Giambattista Basile, who longs to write in his own Neapolitan dialect and thereby give it some literary status of its own. (The Tale Of Tales is, in fact, written in Neapolitan dialect — quite different from modern Tuscan-derived Italian.). For purposes of the show, I imagined that English lyrics represented Basile’s own Neapolitan dialect, while Italian lyrics were the literary Tuscan language.

Bottom line — I tried my hand at writing some lyrics in Italian… and I found an online Italian rhyming dictionary to help. (Good news — lots of things rhyme in Italian!)

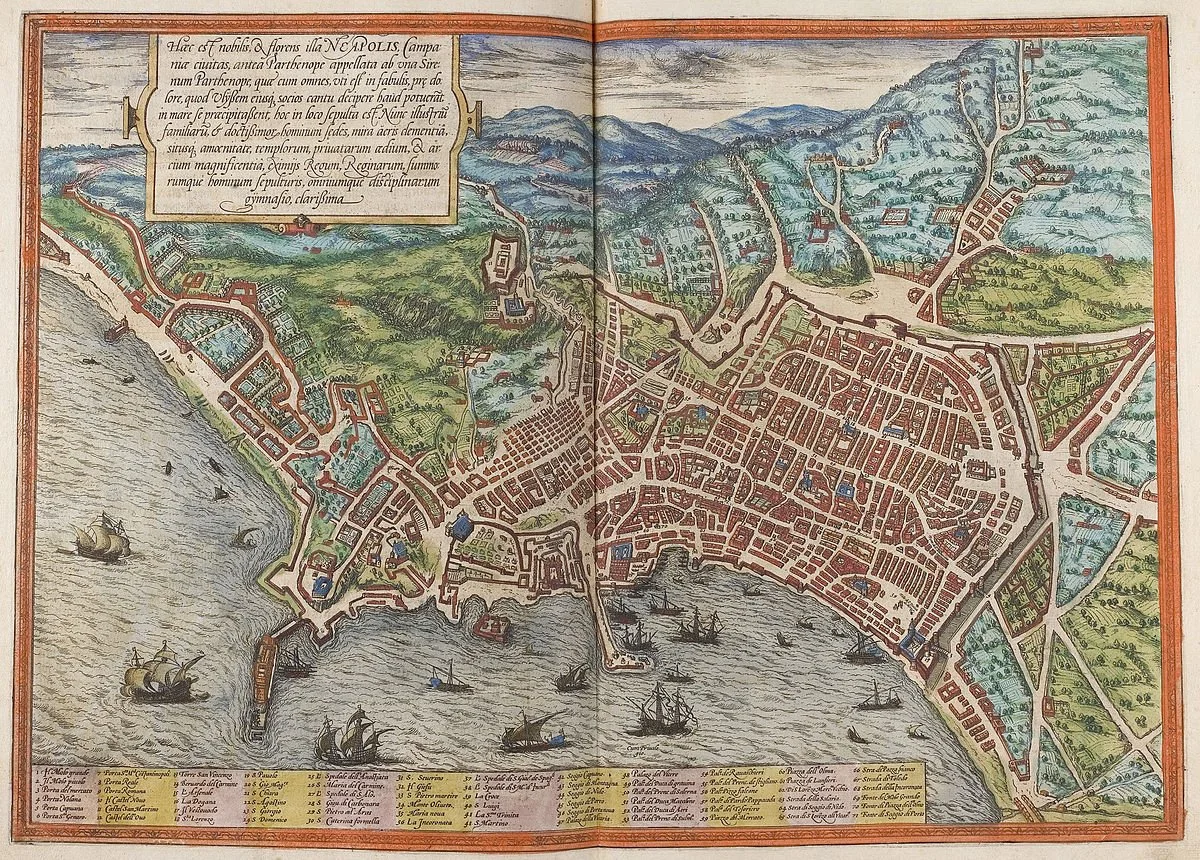

Okay, I’ll admit it: this title occurred to me about ten seconds after first considering the idea of a show about fairy tales from southern Italy. The heroes of the story, the Basiles, were born and raised in the Naples area. And, as mentioned above, Giambattista was very concerned with elevating his native culture and dialect. So I knew Naples was going to be not only an important setting but almost a character in the story — and I thought it was worth having a song about that.

In researching Naples, I learned that during the Basiles’ time (which was roughly the same as Shakespeare’s) the city was under the control of the Spanish. This led me to think about Man Of La Mancha, since Cervantes was another roughly contemporary figure. In listening to Neapolitan folk music, I had definitely heard the Spanish influence, and decided that I might lean into it for the song about Naples. This, combined with the song title I was already set on, led to the hemiola rhythm that drives the song. The earliest idea I had for it was the rhythmic setting of that title, with the sharp accents… “NA-po-li EV-er AF-TER” — kinda like “I want to BE in a-ME-RI-CA”. But also, I had noticed that the Spanish-infused Neapolitan folk music often did really complex things shifting between duple and triple subdivisions. That’s what led me to the 10/8 setting of the title phrase (while the rest of the song lives in a more normal 3/4).

Lyrically, the main idea was history, and the idea that many, many peoples had lived in and ruled over Naples… that the different regimes were transitory while the city itself was eternal — thus the “ever after” from my title. So rhyming and alliterating all those different eras of Neapolitan history was fun. But probably my favorite lyrics in this song are from the bridge — where the game became finding American phrases to rhyme Italian words, “piazze” “scugnizzi” “mezzo” and so on.

Giambattista Basile, author of The Tale Of Tales, is the main character of our musical — so I wanted him to have an “I Want” song, as per BMI Lehman Engel rules. Early on, I’d stumbled upon a phrase provided by Basile himself, in a dedication he wrote for Cortese, a fellow writer’s book, wherein he describes how writers like himself and Cortese all serve the “king of the wind” — because their work amounts to nothing… vanishes into the thin air. And I thought that clearly this was a man after my own heart. Not only could I relate to the struggling writer, but I’d already written several shows about characters like this (to the point where Cara and I had vowed “no more shows about writers”… but then had to make an exception for this project.)

Anyway, the phrase seemed perfect for my purposes. And for some reason, it took me to a more contemporary musical theater place. I started off with a more Baroque sound, but when it gets to the chorus… it just felt like it needed to rock out a bit. This is the closest thing the show has to a “lift-able” song that might be cool to sing out of context — but even then, it’s a little too nerdy and specific to do that.

Most of the musical was a telling of Giambattista and Adriana Basile’s life stories. But, in the spirit of “The Tale Of Tales,” the show did include a show-within-the-show: one of Basile’s actual tales. I decided that the best one to use would be “Nennillo and Nennella” — which is a version of Hansel and Gretel — because the story concerns a brother and sister, divided by circumstances, and then happily reunited. This would echo the story we were telling about Giambattista and Adriana: how, after struggling to find a patron in Naples, Giambattista decides that he must leave his native city and his sister behind and go seek his fortune abroad. While Giambattista is abroad, Adriana achieves the success in Naples that her brother never could, and so she summons him home because she has been able to secure him a position at court. In the musical, this bit of narrative from the Basiles’ biography is threaded in between the three parts of the Nennillo and Nennella fairy tale.

An irony of the story of Giambattista and Adriana is that history now remembers him, while she has fallen into obscurity. But during their lives, Adriana was a huge star (our joke was “Ad-Rihanna”), and it was her clout and wealth that allowed her to publish The Tale Of Tales after Giambattista’s death. In this reprise of “King Of The Wind,” Adriana finds her brother moping about how all of his writing seems to come to nothing, and she reminds him that as a singer, her art is even more ephemeral.

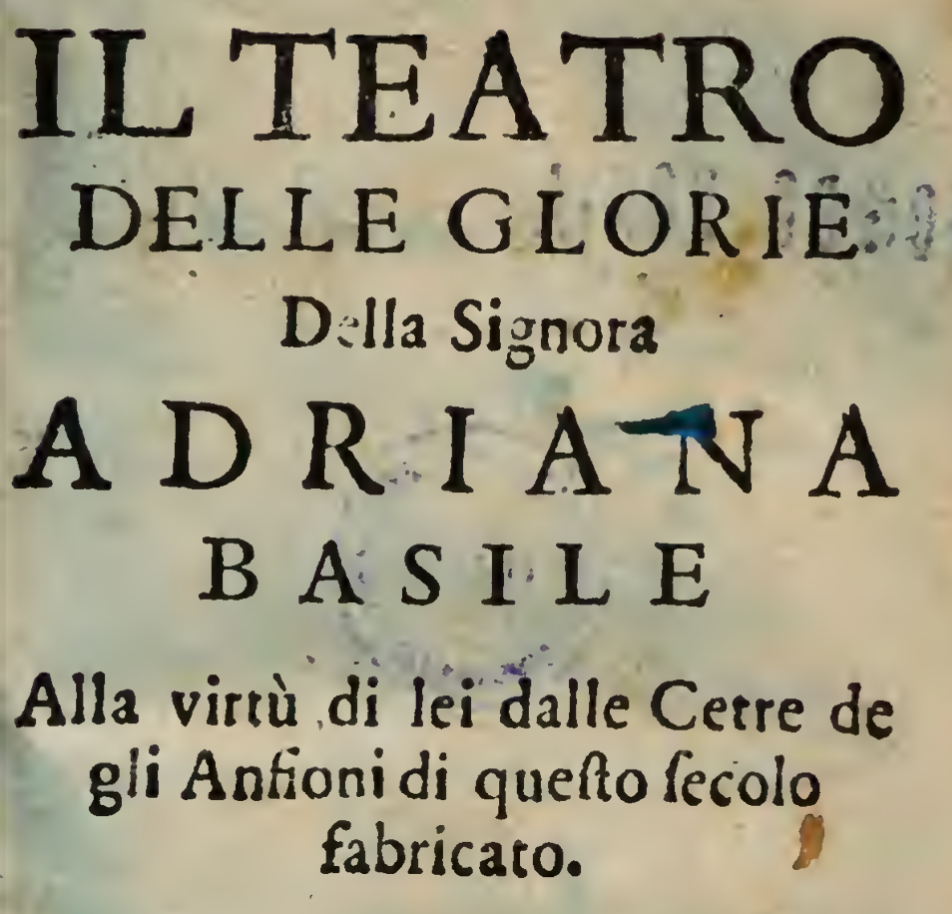

And Adriana was right: her legacy has vanished because we have no sound recordings of her voice. All we have are the testimonials of those who heard her perform… and we have a lot of those, thanks to Adriana’s own efforts. Like any successful idol, Adriana was a very shrewd cultivater of her own image. She created and burnished the legend of Adriana Basile, “The Siren Of Posillipo.” (That’s the name of the Neapolitan suburb where she and Giambattista were born.) She collected all the praise and hype lavished upon her (these usually took the form of short poems written by various noble lords for whom she performed) and gathered it in a book, which she published herself:

That translates to :

“The theater of the glories of Signora Adriana Basile” and the book was filled with hundreds of poems written by dukes and princes and marquises… and even a few by her brother Giambattista.

All of this was fantastic fodder for another song I wrote with Italian lyrics. The poems in praise of Adriana were all written in “literary” (Tuscan) Italian — and so, by the rules I explained above, these song lyrics were in Italian. In “Quando Canta Adriana,” the rapturous nobles try to put into words the experience of hearing Adriana sing.

In the early 17th century, Mantua was a musical Mecca. Duke Vincenzo Gonzaga was a lover of music and made it his project to gather all of the finest musicians of his day and age at his court. Naturally, when word reached him about the extraordinary Adriana, he had to have her — and, after a lengthy negotiation, he finally persuaded her to come to Mantua. There, she was set up like a queen, and was the undisputed star of Duke Vincenzo’s collection of virtuosi.

Among those who had also been brought to Mantua was the composer Claudio Monteverdi — who would go on to become more famous than either Adriana or her brother. Nevertheless, Monteverdi rated only a fraction of what Adriana was paid.

At one point in our musical’s story, Giambattista comes to visit Adriana at Mantua. And there, we imagine a meeting with Monteverdi: Giambattista confesses how he is still struggling to find his voice as an artist. Monteverdi, who around this time, had boldly broken with musical tradition to create what he called “Seconda Prattica” — essentially, new rules for the music he wanted to write — counsels Giambattista to trust his intuitions and write what is “true to him.”

I took the melody for Monteverdi’s song from the opening of the composer’s Orfeo:

Making a satisfying a dramatic arc from a writer’s life story is always challenging. (As I mentioned, I’ve tried it several times….). For Giambattista, the theme of the story seemed to be this question of whether his work mattered, whether he would be remembered. This was the question raised by his “I Want” song, “King Of The Wind.” So it seemed like the end of the story should answer this question.

An interesting part of the research into The Tale Of Tales, was discovering the earlier versions of many of the most famous fairy tales — like Hansel and Gretel, and Puss In Boots, and Rapunzel, and Sleeping Beauty, and, yes, Cinderella. All of these fairy tales are better known through the versions written down by Charles Perrault or the Brothers Grimm. But Giambattista had gotten there first! And in the case of the Grimms, the brothers were well aware of this, and had made a study of Basile’s work, and even worked on translating his tales.

The Brothers Grimm

Giambattista never saw his tales published, and never knew the legacy that they would have. But I found it comforting to imagine a scene where Basile, on his deathbed, is visited by the literary ghosts of all the future fairy tale tellers who would follow in his footsteps. And so, this became the premise for the musical’s “eleven o’ clock” number, “Cinderella Story.” The song was a lot of fun to write — getting back to my roots writing goofy, high-concept songs for the Princeton Triangle Club, which was appropriate since many of the students in the show were also from the Triangle Club. The song was also like a pep talk for Pete the writer, reminding myself that it’s always possible for a writer to be re-discovered in posterity. So, you never know… your work might matter after all!

PS — favorite lyric in this one? “Now we’ve given you the proof it’s got merit / Now we’ve shown you that the shoe fits, so wear it.” Though, Sondheim would probably have said “merit” and “wear it” don’t rhyme. There’s a story…